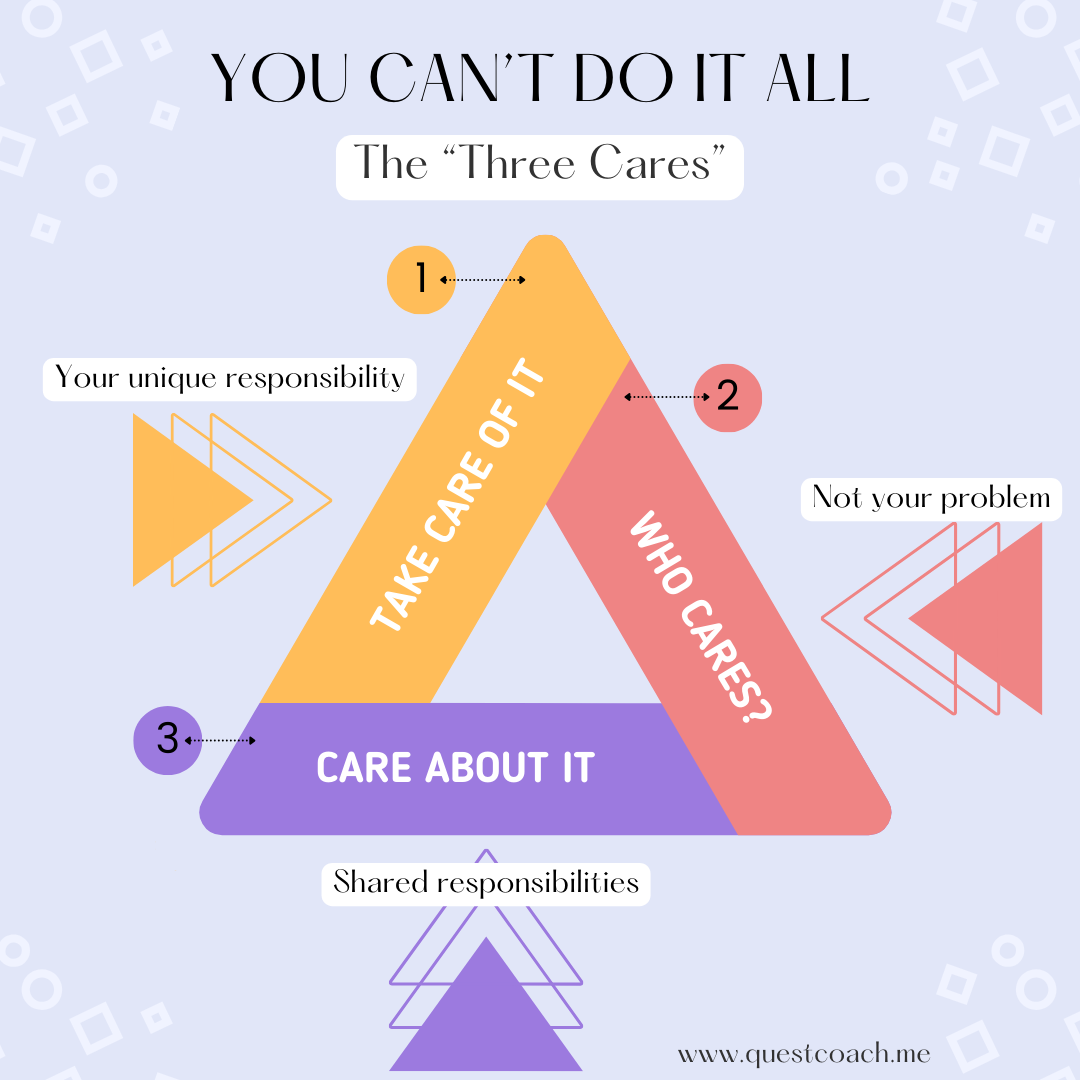

The Three Cares

What’s the difference between caring about a thing (or a person, or people), and caring for them?

Which one are you doing? How do you know if it’s the kind of care the situation needs?

A leader who doesn’t care about the people they lead, the organization they’re in, or their collective success is probably not a very good leader. Indeed, being careless is almost never a compliment.

Care is, after all, one of the things we tend to look for in people we want to be (and work) around; it tells us that they have a stake in the same things we have a stake in. Maybe most importantly, it suggests that they have a stake in us and our accomplishments. The fact that they care about us and the things we care about builds a sense of shared purpose and shared responsibility, which are hallmarks of success in almost every area of life.

A good friend and colleague of mine came to me last week feeling completely overwhelmed. She had taken on a leadership position a year before, supervising a team of 20 which quickly ballooned to 40. She was glad to have gotten more resources, but soon found that the promise that she would be able to hire subordinate leaders to help her manage the team and its mission would not be fulfilled. Another key team member took a career-advancing position in another area, leaving her with even less support than she started with. She cared deeply for the organization’s mission, and for its success. Nevertheless, she felt like the excitement and joy she once felt to be part of something she believed in was now completely out of reach.

Time that she might have used to recharge at home with her husband and stepson was similarly challenging. Almost all of the household responsibilities and child-rearing duties fell to her, as well. Cooking, cleaning, budgeting, homework help, negotiating schedules with her husband’s ex – it almost all fell to her to do, or it simply would not get done.

Honestly, she’s a pretty amazing person – as long as everything was going well, she could handle it. She might not be happy, but she was undoubtedly productive and unflinchingly responsible.

One day, one of her team members experienced a sudden unforeseeable health event in the office and had to be hospitalized. Her boss was furious both that the disruption would impact team productivity, and that she had not somehow anticipated and handled the health scare on her own. “You should have known better!” he said. And that’s when my friend, for the first time, felt herself wanting to give up.

As we talked about all the things that had happened, realization struck: care can go too far, at least at work.

There are certainly people and things in our lives we need to care for – we can’t share responsibility because they’re kids, or aging parents, or an ill significant other…or any number of other things. We also call that taking care: we pull the burden of responsibility onto ourselves because they can’t reasonably be expected to share the load equally with us. We care because they can’t, won’t, or so they don’t have to.

My friend had been taking care of more and more things at work and at home, and the people around her, especially her superiors at work, had happily played along – she was willing to take care of everything, and they were happy to let responsibilities pile up on her plate. Meanwhile, the people who worked for her were, in some cases, feeling shut out from the organization’s core tasks and functions. They wanted to share responsibility (and recognition) for success, but found themselves struggling to identify opportunities to step in or step up. Over time, she wondered, had this led some of her best employees to disengage and ultimately leave the team?

Her ability and willingness to care, normally a positive, had been stretched out of shape to become a negative. Instead of caring about the team’s success as part of a collective effort, she was caring for them – instead of them, even. Organizational psychologists like those at Hogan Assessment Systems would call this a “de-railer”; coaches with different backgrounds sometimes instead refer to these maladaptive traits and behaviors as “saboteurs.” No matter how we name it, it was clear that my friend needed something to change.

In the end, we decided to set up a challenge. I asked my friend to do the following:

“Take Care of It.” Identify three things, and only three things, that by position, skill, or ability, should be primarily or exclusively hers to care for.

“Who Cares?” Identify three things, and it must be at least three things, that she could stop caring about. They might be things that nobody really needed to take care of, or things that someone else was better suited to “own.”

“Care About It.” Finally, I asked her to identify three things that she must share responsibility for. She could still care about them, but these were the things that everyone needed to have a stake in to make her team (or her family) work.

I challenge you to give this a try yourself. What’s on your list of three cares? What’s on the wrong list?

Maybe you’d like some help working through this, or something like it?

Quest Coaching is here to help.