Groups, Change, & Orcs

How’s your team doing?

Where are you, right now, in the group development cycle at your job? In your family? In your circle of friends?

Is there a place where a member of your personal fellowship is stuck, unable to contribute to your common goals?

What’s one thing you can do, today, to help get them unstuck?

Where are they facing hordes of orcs and winning?

Where are the orcs getting the better of them, and you?

Let me explain.

A few months back, I left a leadership position in one small, relatively homogenous, close-knit team, and took a new job as the chief of a much larger, much more diverse organization. It was a great opportunity for me, but leaving the team I had known was hard.

Over my time in that previous position, I had experienced conflict both within the team and between the team and its peers and leaders; I had adapted my approach and helped the team adapt its way of working to better “fit” my bosses’ vision, and as I sought training, mentorship, and gained familiarity with what they did was eventually able to directly contribute to our work products, even though I was technically a manager who could at best consider himself an enthusiastic amateur among highly trained professionals. Still, that process of learning eventually gave me enough understanding of the unique challenges and opportunities my niche team were facing to be able to effectively advocate for and with them to higher-level leadership, and to “sell” our products and services to clients and customers.

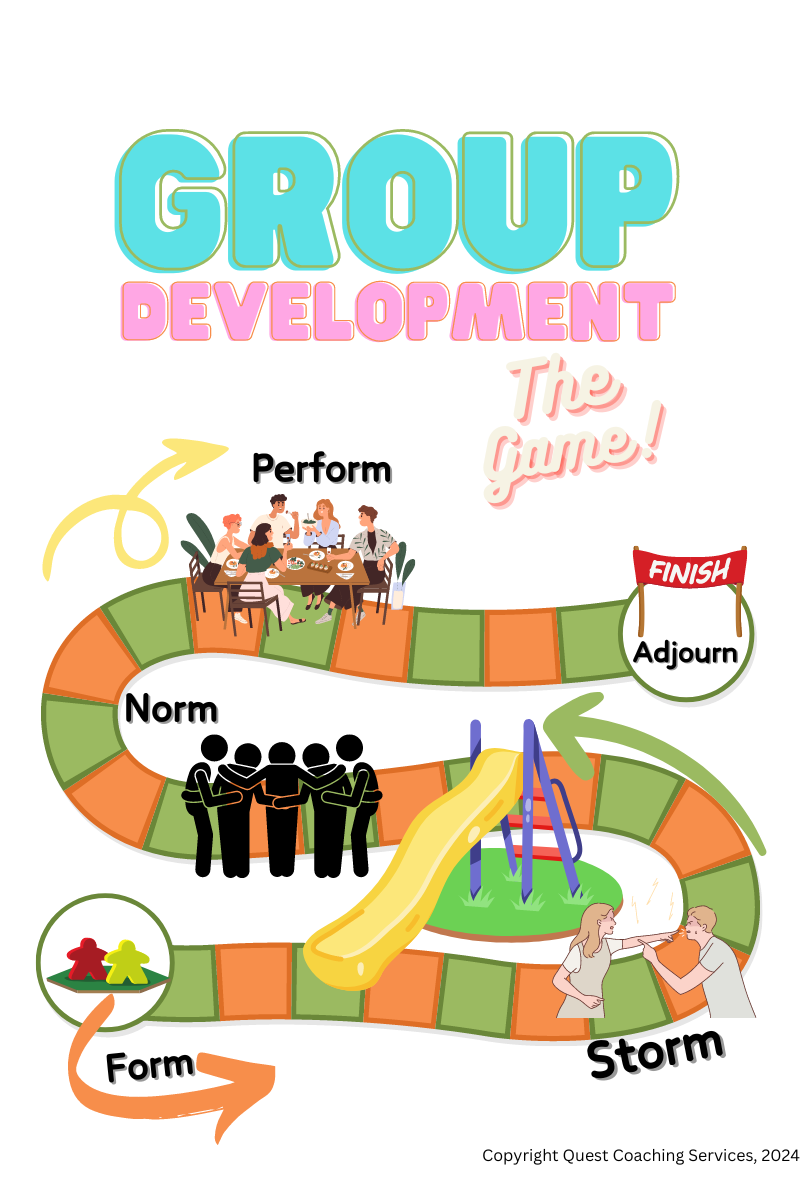

I had, in essence, lived through a conveniently rhyming model of group/team development that American psychologist Bruce Tuckman developed in the 1960s:

Form (initial orientation, getting to know each other; typically very polite and formal)

Storm (conflict, competition for dominance, roles, and influence; formality begins to fall away)

Norm (settling, cohesion, and collaboration; group latches on to common values and purpose, training and upskilling become possible/practical at this phase)

Perform (effective teamwork, task completion, and achievement; group is most resilient and flexible here)

…and then, as I moved to my new team, I lived through the fifth stage (which almost, but does not quite, rhyme with the first four):

Adjourn (the group’s purpose is fulfilled; [some] stakeholders move on, and the group[s] returns to start)

Whether you’ve been conscious of it or not, you’ve almost certainly been through this yourself. Even fictional characters go through this process!

In my own career, I’ve benefited a lot from going through (and leading others through) Tuckman’s process again, again, and again...though thankfully my teams haven’t had to endure any orc attacks. Yet. In my most recent opportunity, even though the larger team I was now leading had been in place in one form or another for at least 15 years before I got there, my presence forced the group to adapt. You see, every change – whether addition, subtraction, or trade – to a group’s make-up kicks off a fresh cycle.

As if to make an already complicated thing even more complicated, people in the group are moving through these stages at different rates. Small changes in membership, task organization, or unexpected risks and opportunities can usually be absorbed and adapted to quickly, if the group is overall far enough along in its development. New members experience the full cycle alongside their more settled fellows; even well-established members of your fellowship might decide to buck group norms, disrupt trust and performance, and try to take the (metaphorical?) ring for themselves when an irresistible opportunity arrives…like Boromir. Regardless, the larger the change – or the larger the accumulation of small changes – the more likely it is that the challenge will knock the bulk of the group into early adjournment or back into the form stage.

The Orcs…of Change. Or something.

Part of leading your group — whether family, friends, or coworkers — is managing (but not necessarily slowing or stopping) the scale and scope of change happening at any given time, so that the group and its members can run through the cycle and return to the perform stage as quickly and painlessly as possible.

When you were born, your family probably spent some time adjusting to your presence; if you’re a first or only child, the form stage was probably pretty lengthy for you and your parents or guardians. I am willing to bet, however, that no matter how good a kid you were, at some point your caregivers hit the storm phase and had at least one argument about how to handle some new challenge you presented. By the time you were in school, they had established expectations that let them function as humans while still caring for you (and each other)...and then eventually you moved out of the house (adjourned).

If you have one or more siblings, you can probably remember what it was like to have members of your group (family) all in different stages of Tuckman’s model at the same time: a baby brother or sister knocks the whole system back to forming and storming. After they were born, you and your parents recovered equilibrium (norm) a lot faster than the baby, which spends its formative years storming through developmental milestones before beginning to develop enough of a distinct identity and personality to advance toward norm and perform.

Bottom line: this cycle happens, and it’s happening all around you all the time. Becoming aware of it gives you an opportunity to lead yourself and others through it more deliberately, and hopefully more successfully.

Wherever you are in your journey, whether there or back again, we’re here to help.

If nothing else, you might need someone to help you watch out for orcs.